The arrow of time is a concept of physics, developed in 1927 by British astrophysicist Arthur Eddington, which explores the nature of time’s linearity. It addresses the fact that, unlike space, time cannot be rearranged; we are forced to move forward with it in one direction.

Christopher Nolan’s own pull to this concept has defined his cinematic portfolio and reputation as one of history’s greatest directors. From warped alternative realities to historical biopics set in the time-reality we know, Nolan consistently returns to his hallmark fixation to pose the idea that time is anything but linear.

Nolan’s Approach

It’s worth noting that any film which captures a narrative exceeding its own runtime demands the reorganisation of time. As Nolan himself says, “the sense of time in conventional films is very distorted,” involving compressed timeframes, narrative gaps, and switching perspectives. Stories in any format are merely a symbol of experience, so they’re not bound to the same laws and patterns as experience itself. From flipping back and forth, zoning in on certain details to withholding others, stories are often at their best when their timelines depart from reality. Apart from certain anomalies like Locke (2013), we accept that storytelling in film necessitates breaking the arrow of time.

What makes Nolan’s films unique is not necessarily their distortion of time, but their use of this distortion to highlight the illusion of experience. As a fact of existence, time may seem easy to comprehend, yet it still confuses and overwhelms us as a lived experience. How is it that time—constant and unwavering—can feel so messy, brutal and unstable? It is through these kinds of questions that Nolan seeks to explore how being human subverts Eddington’s arrow of time. For Nolan, the distortion of time is not just a symptom of filmmaking, but a central theme through which he seeks to pose these questions— and not necessarily answer them.

Rather than following time-linear structures, Nolan treats each of his films as a sum of its parts, which allows him to break the arrow of time, and arrange his scenes according to other patterns more relevant to his narrative. For example, a scene from one timeline may be succeeded by a memory which has informed it, which draws attention to the way that the past is constantly spilling into our present.

Dunkirk (2017)

Equally, these cinematic techniques exist to support a narrative pinned around suspense. In Dunkirk (2017), we see three timelines unfold alongside one another— one week on land, one day at sea, and one hour in the air. As Nolan himself notes, “as one storyline is peaking, another one is building, and the third one is just starting out,” which maintains a continuous rise in intensity.

Here, the arrow of time is subverted to evoke a sense of chaos and nervousness. Everything leads up to a final climax, and the timelines all play on our collective fear of time running out, emphasised by the constant sound of a ticking clock. Minutes feel like hours, and hours feel like seconds. The hour in the air involves a “very focused timescale that stretches and makes that hour feel overwhelming,” whilst the week on land feels intense in a different way; time feels like an endless limbo, a long corridor where salvation is always just out of reach. The camera angles and filming locations support these subjective experiences, the narrow cockpit contrasting with the endless, barren beach.

As Nolan says, “with each strand, you’re telling the story intensively subjectively.” In other words, each perspective serves only a narrow view, revealing each characters’ specific fears about time. But this also reflects the way that we collect knowledge and understanding of global events, piecing together multiple accounts that come together into a bigger picture. Once events have fallen out of the present moment, they tend to converge into what we think of as ‘eras’ or ‘chapters’ in time— often thousands of accounts and timelines that serve a single story, distinctly non-linear.

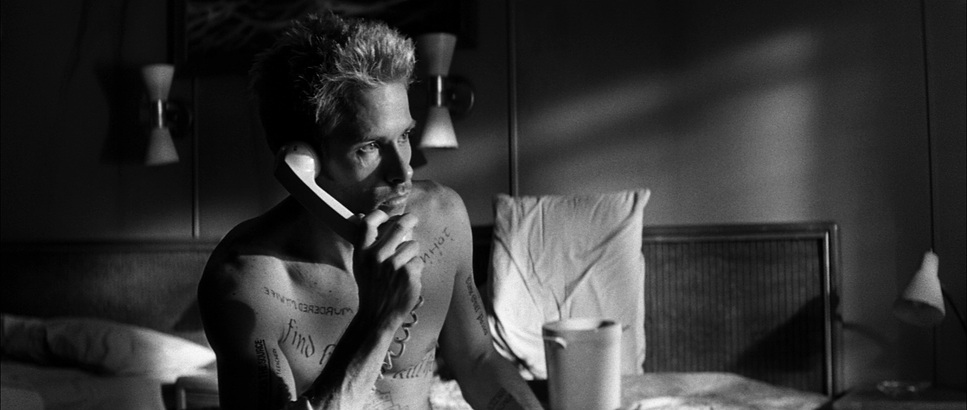

Memento (2000)

From disorienting dreams to unreliable memories, the way that we recall our lived experiences is anything but objective. As Leonard (Guy Pearce), in Memento (2000), says, “memories can change the shape of a room” or “change the colour of a car,” and they regularly misalign our experience of time. This revelation isn’t to refute the existence of time’s arrow, but rather to place it in the context of our own subjective reality.

In what would come to define his succeeding career, Memento showed us Nolan’s ability to subvert the audience’s understanding of time’s linearity. A story told in reverse, Memento “contradicts the philosophic principle of what time is: the co-presence of different pasts in the current moment rather than a series of succeeding ‘now’ points” (UKEssays, 2018). By feeding us continuous plot puzzles and placing us in the mind of a man with anterograde amnesia, Nolan forces us to grapple with a feeling of existential confusion.

Dreams, memories, and our minds’ constructions of our personal narratives all push and pull with our understanding of the passage of time. Time seems to swell and constrict, whilst our own memories deceive us. The fact is, memories are “just an interpretation. They’re not a record,” as Leonard in Memento so profoundly states.

Interstellar (2014)

Nolan has said that working within the science fiction genre in particular affords him the ability to explore these collective fears in a more exaggerated way. It’s no surprise then that his obsession with time reveals itself most blatantly in the likes of Interstellar (2014), where we see Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) come face-to-face with the physical presentation of time’s arrow.

Interestingly though, it is often this exaggerated distortion of time that makes Nolan’s films so relatable. Cooper watching his son’s video logs in Interstellar is heartbreaking, as it materialises the inexplicable feeling that our lives have been slipping away without us. Nolan takes these everyday illusions and visualises them as realities, which helps connect us to his characters and far away worlds.

Our protagonists, often facing pursuits that could change the course of life as we know it, face the very mortal burdens of regret, guilt and longing. Using suspense and desperation, Nolan creates immersion in his films by relating his narratives to our own obsession with the ticking clock.

Inception (2010)

Dreams too are prone to departing us from our own realities. Like Interstellar, Inception (2010) plays on the notion of time dilation, with the passage of time slowing exponentially as you descend into deeper layers of dreams. Time dilation is a phenomena that fares well in science fiction, but it’s also an experience that we can relate to in our everyday lives. Time seems to halt in a crisis—when you drop a glass or fall over on the street, the seconds seem to swell as time slows down.

“Dreams feel real while we’re in them. It’s only when we wake up that we realise something was actually strange.”, Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) says. We may accept that our own experiences of time dilation and dreams are a physiological illusion, but Nolan blurs the lines between life and sci-fi by posing the question: what isn’t? Experience is inherently subjective, and this complicates the notion of an objective reality.

Nolan nods to these postmodern ideas in almost all of his films, reminding us that ‘truth’ is not a fixed state, and that we should be more cautious about trying to assign objectivity to our inherently subjective experiences. In this way, the pace and time manipulation of Nolan’s films reflects our inherently loose grasp on our own narratives, fighting against the scope of time and its ability to deceive us.

Tenet (2020)

Anyone who’s watched Tenet (2020) will appreciate the benefit of coming back to Nolan’s films a second (or tenth) time, and this pull is an intentional aspect of his work. As early back as 2004, Nolan was talking about his draw to films that begged to be returned to. He strives to create narratives that offer different experiences upon subsequent watches.

Forcing us to reinterpret everything as it unfolds, Nolan’s films often make us doubt our own comprehension of them. The experience is one of intrigue, but sometimes also of frustration. For many, Tenet taunted its audience in this way at the sacrifice of its own narrative, and this can be the risk of trying to relay new translations of time within a cinematic piece.

Nevertheless, Tenet engages with Eddington’s arrow of time more directly than any of his other films, exploring a hypothetical world where the flow of entropy (and thus ‘time’) can be inverted and reversed. Using this concept to explore themes of free will and determinism, Tenet presents a thought experiment about not only the arrow of time, but also our social responsibility to protect our collective future. Its themes are unapologetically complicated, but desperate to possess some form of clarity, our torment exposes the ideas that Nolan intends to reflect— the hopeless and incessant search for objectivity and perfect preservation.

Conclusion

Nolan is less concerned with audiences’ understanding and seeks instead to connect us to his characters through our shared ignorance. In fact, he encourages that “you’re not meant to understand every single aspect” of his films, but rather “you’re meant to go on the journey, pass through the maze, understand the things you need to understand.” We are unfolding the narrative alongside his characters, forcing our thoughts and analysis to mirror theirs.

Using experiences like memories, dreams and deliberate concealment of the wider picture to place us in their minds, Nolan forces us to grapple with the inherently disorienting experience of being human. “You’re not sitting above it, watching the characters make wrong turns; you’re down there, in the maze, making the wrong turns with the character,” Nolan notes. It is perhaps only in retrospect that we can relate the story to our own fear of time and fragility, as we come out imprinted with the experience of the characters on screen.

The modern world demands objectivity, and developments in science and technology have afforded us an unprecedented grasp on our own reality. But Nolan’s films are a reminder to remain curious, and to seek questions as much as we do answers. Exploring the relativity of time and our subjective experiences as humans, Nolan has been celebrated for his “realistic engagement with physics” and philosophical debate. However, his greatest achievement is the ability to relate these concepts to the everyday.

Nolan’s stories seem to follow obsessive pursuits for objective ‘truth,’ but his narratives lead us through turns that eventually emphasise the importance of embracing uncertainty— of extending hope into the unknown and trusting in that which we don’t understand.

Works cited:

- Howard, J. (2017) I Love Christopher Nolan, YouTube

- IGN (2017) Christopher Nolan Explains Dunkirk’s Unique Structure, YouTube

- UKEssays. (2018) Time and Space Manipulation in Christopher Nolan’s Memento

- BBC Newsnight (2015) Christopher Nolan: The Full Interview, YouTube

- FilMagicians (2017) Memento – Interview with Christopher Nolan (2004), YouTube

- NPR (2020) Christopher Nolan On Why Time Is A Recurring Theme In His Movies

- Winterhalter, B. (2021) “Tenet” isn’t Paradoxical – It’s Christopher Nolan on Climate Change, The Philosophical Salon

Leave a comment