Mario Bava (1914-1980) was a pioneering filmmaker, cinematographer, director, producer, screenwriter, and special effects artist. Undoubtedly ahead of his time, Bava crafted some of the most compelling visuals, and—amongst other contributions—had a vital role in the evolution of the modern horror film. His distinctive style also inspired Dario Argento, Jennifer Kent, Quentin Tarantino and Nicolas Winding Refn, among many others.

Born in Sanremo, Italy, to cinematographer, sculptor, and special effects artist Eugenio Bava, the younger Bava initially studied painting before following in his father’s footsteps. His skill within the film industry became apparent early on, as he was regularly assigned the task of completing work begun by or credited to other professionals who had left productions early, including I Vampiri (1957), Italy’s first horror film of the sound era. This reliable side of the Italian impressed producers, and his adeptness despite various challenges would continue throughout his career. Although Bava frequently worked under stressful conditions where production costs were notably limited, his determination to create beauty without compromise resulted in him crafting works that regularly looked beyond their cost.

From spaghetti westerns and sword-and-sandals adventures to nightmarish thrillers and science fiction, Bava did not hesitate to explore diverse genres throughout his long career. Across his varied filmography, viewers will find that the common denominator was his ability to create a world worth investing time into beyond the stories themselves. Since Bava first and foremost approached the medium in terms of visual language due to his background, a notable characteristic of his style was his meticulous eye for details within each frame. As he recognised the value in crafting engrossing mise-en-scène, Bava invariably excelled at creating a particular presence in his work that is alluring and eerie, but always recognisable. With a penchant for dreamlike atmospheres, he crafted memorable visuals, all accented by his distinctive use of colour, masterful manoeuvring of lighting and overall technical ingenuity.

Bava’s first official solo feature directorial effort was Black Sunday (1960), a gothic horror film demonstrating how technically competent the filmmaker was through its chiaroscuro lighting. He went on to direct various works, including Planet of the Vampires, Hatchet for the Honeymoon, Lisa and the Devil and Shock. Despite Bava’s reputation as a talented filmmaker during his lifetime, most of his films failed to achieve major commercial success upon initial release. Instead, the greater part of praise arrived gradually and retrospectively, with many films gaining cult status. To commemorate the 110th anniversary of his birth, this list seeks to acknowledge and celebrate the filmmaker’s everlasting originality and extensive skill. The selection of films condenses Bava’s artistry into five films that all encapsulate elements of his versatile craftsmanship and the legacy left behind.

A Bay of Blood (1971)

Following the mysterious death of a wealthy countess, greedy people pull all kinds of shady schemes to try and gain control of the late woman’s assets. What ensues is a murder spree, unravelling at a coveted secluded estate as a myriad of selfish parties emerge, only to be subjected to torturous consequences. Death after death, the film quickly sets up the scenario that no one is safe and that anyone could be the culprit. While Bava in Black Sabbath (1963) employed what is now considered a classic horror premise (a woman, home alone, begins to receive threatening phone calls), the potency of A Bay of Blood (original title: Ecologia del delitto) is even more prominent as it can be considered a blueprint for the slasher subgenre that would later follow.

A vital watch for any fan of the genre, A Bay of Blood features elements viewers would soon think of as staples, including grisly kills captured in visually inventive ways, frivolous young adults, and a high body count. Moreover, individual kills would also prove influential, as seen in Friday the 13th Part 2 (1981), which pays homage to two of the film’s kills. Also known by the titles Blood Bath, Carnage, and Twitch of the Death Nerve, A Bay of Blood is undoubtedly one of Bava’s more violent. It should not come as a surprise then that the film’s unflinching emphasis on graphic gore tested the boundaries of censorship at its time of release; for instance, in the UK, the film was associated with the infamous “video nasties” list and was subsequently prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act.

Written by Bava, Giuseppe Zaccariello and Filippo Ottoni, the screenplay offers more than solely violence. While a lot of focus surrounding the film centres on how it came to be influential, more should be said about its ending. When discussing Bava’s work, the emphasis is often on visual inventiveness. However, it is worth underlining that his style does not equal a lack of substance. Bava’s films frequently explored society’s shortcomings by focusing on traits like greed and selfishness. Beyond its gore, the film is unforgettable due to its finish, a brutally bleak punchline that aligns with the overall examination of human destructiveness. Although less stylised than other instalments in his filmography, A Bay of Blood still features Bava’s signature in being well shot, including a seamless match cut from a human decapitation to a doll’s head. This, in combination with the expertise in all things gruesome by acclaimed special effects artist Carlo Rambaldi, results in a compellingly raw viciousness that feels contemporary to this day.

Blood and Black Lace (1964)

A quintessential film for any giallo fan, Blood and Black Lace (original title: Sei donne per l’assassino) begins on a stormy night on the grounds of a fashion house when a model is murdered by a masked assailant. As the police commence their investigation, the victim’s previously unknown diary detailing the many vices of the company and its employees emerges. Desperation erupts and killings increase as everyone, including the faceless killer, wants to gain control of the scandal-revealing diary to prevent its secrets from being revealed.

Although Bava’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963) is often credited as the first giallo film, Blood and Black Lace helped establish the bold use of colour and more graphically violent murder-mystery template that would later define the genre. The film’s cultural importance also extends to Pedro Almodóvar, who references one of the murder scenes in the opening of Matador (1986). In his decision to eschew the more traditional mystery in favour of a more explicit kind of suspense, Bava managed to create a distinct ambience that is impossible not to be enchanted by. Moreover, the decision to hide the menacing villain’s identity by using tightly fitted fabric over their face is surprisingly effective. While using masks to hide someone’s identity is not new, the clinical emptiness of the monochromatic fabric underlines the disturbing idea that anyone could be beneath it.

From its sultry opening credits until its dramatic end, the film is a visual triumph. Featuring artistry that is a treat for any viewer, it showcases some of the most beautiful images in cinematic history. Whether it is the depth of shadows or the vibrancy in its green, purple and red hues, Blood and Black Lace captivates its viewers by creating a sort of dreamlike state. Besides being a technical achievement, Bava’s meticulous eye for detail is highly engrossing here. The filmmaker took full advantage of the fashion house setting, using everything from eye-catching costumes to carefully embellished sets in crafting memorable frames. Even though the act of combining beauty with the macabre was nothing new for the Italian, here it adds to the story since it all unravels within an industry focused on selling pretty surfaces. Beneath the beauty lies—individually and collectively—human corruption and immoral impulses. In combination with an abundance of blackmail, red herrings and secrets, the story features a claustrophobic thread that runs through the film’s fabric to affect the viewing experience.

Danger: Diabolik (1968)

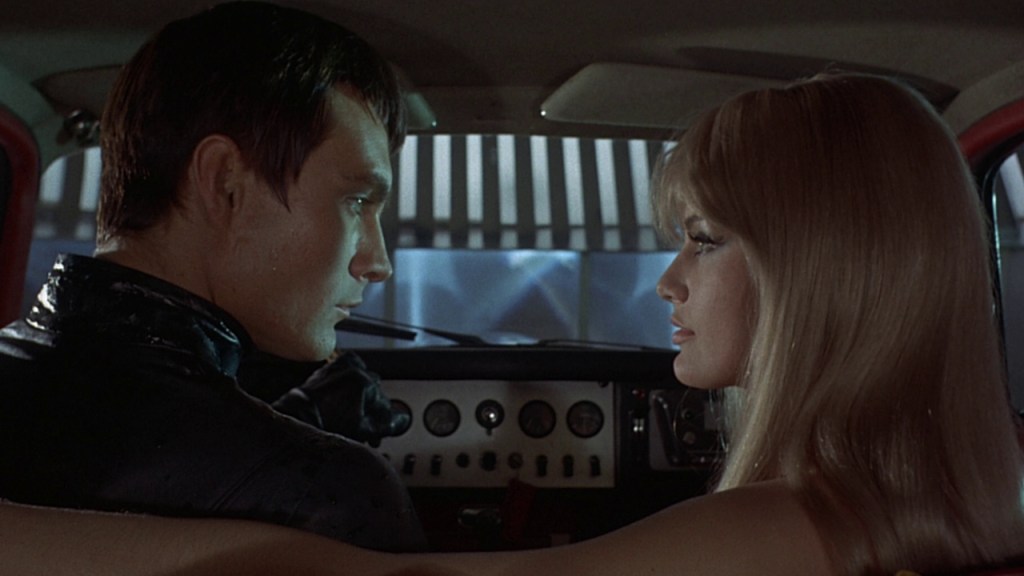

Based on the Italian comic series Diabolik by Angela and Luciana Giussani, Danger: Diabolik follows master thief Diabolik (John Phillip Law) and his lover and accomplice Eva Kant (Marisa Mell) as they carry out large-scale heists just for the fun of it. However, their carefree way of living might soon come to a halt as Inspector Ginko (Michel Piccoli) teams up with an unlikely partner in an attempt to catch them once and for all. With a script by Bava, Dino Maiuri, Brian Degas, and Tudor Gates, Danger: Diabolik is an intoxicating Euro-flavoured pop-culture spectacle that echoes elements of Arsène Lupin, James Bond, and the 1960s live-action Batman television series.

Similarly to other titles in Bava’s filmography, the film was not a success during its initial release but has since become a cult classic due to its distinct look and the director’s signature creative imaginativeness despite a low budget. Through its mise-en-scène, the film attempts to replicate the stylisation of comic books. Besides the fun use of varying camera shots, including whip zooms, Bava regularly uses the frame within the frame technique to draw focus and create dynamic images. Moreover, the decision not to make its action look too realistic only works in the film’s audacious favour. It is very cheeky and riveting—practically everything an adaptation of a comic book should feel like. Besides its delightful visuals, a huge appeal of the film is credited to the sheer audacity of the duo, whose pastimes include repeatedly outsmarting and ridiculing the forces trying to stop them and engaging in passionate sex on top of stolen money in a rotating bed in their underground lair. While not as widely known as some movie couples, Diabolik and Eva are surely worthy of icon status due to their memorable on-screen adventures.

Infectious and exhilarating amoral fun, the cat-and-mouse chase becomes even more entertaining with its bold colours and brilliant production design (the interior of the lair alone makes it worth a watch). A noteworthy accomplishment of this adaptation is its compelling elegance in feeling artificial yet simultaneously sincere. Few films have as much visual identity and personality as Danger: Diabolik, whose campy aesthetic is even referenced in the music video for the Fatboy Slim remix of “Body Movin’” by Beastie Boys. From its funky and vibrant score by Ennio Morricone to its array of meticulous retro-futuristic and mod costumes (Eva’s metal grommet jacket and bikini come to mind, as does a woman’s top made of red plastic triangles connected with metal hinges), Danger: Diabolik is an unforgettable adventure that is as entertaining today as it was then.

Five Dolls for an August Moon (1970)

In Five Dolls for an August Moon (original title: 5 bambole per la luna d’agosto), bourgeois acquaintances have gathered at an isolated villa for a weekend of fun and relaxation. However, as dead bodies start appearing, the guests realise they are trapped on the island with a murderer on the loose, sending them all into a frenzy to figure out who amongst them is responsible. With a riff on a classic premise à la And Then There Were None, the story explores the atrocious acts and selfish behaviours of the wealthy and, even if told in a convoluted way, Bava establishes a particular ambience with a somewhat groovy feel that is enough to make up for the more uneven aspects of the film.

The script was penned by Mario di Nardo, with contributions by Bava. One of his most significant changes includes the idea of putting the corpses in plastic bags inside a walk-in freezer instead of di Nardo’s original plan of underground graves. This change makes for notably creepier images, even more so as it all unravels to a sunlit beachside backdrop that alone does not naturally feel as eerie as darkly lit cobblestone roads or foggy graveyards. However, even though the film features a string of murders, it is significantly less gory than other efforts affiliated with Bava, especially compared to the more brutal A Bay of Blood. Here, the showcased corpses are all associated with murders that occur off-screen. Consequently, for viewers, it is less about the shock of seeing a kill than about the mystery itself.

Although the film is one of the weaker instalments in his filmography, Five Dolls for an August Moon still makes this selection as it highlights how Bava always managed to create something worthwhile. The film’s main issue concerns the script, but beyond that, the whodunit still feels enjoyable due to Bava’s determination to inject his craftsmanship into every frame. Despite its low budget, the film’s striking effects, stylish set design and pleasing cinematography by Bava’s frequent collaborator Antonio Rinaldi deliver something beyond its price tag. Throughout his career, Bava regularly employed a range of effects, including matte paintings and maquettes, to give the illusion of backgrounds and details that otherwise would not exist and to play with the idea of space. An instance of this type of work in the film is the exterior of the villa—a matte painting by Bava himself. Besides a chance for him to fully engage in a medium he loved, the effect also results in enthralling imagery where the object in question pops energetically within the frame.

Kill, Baby… Kill! (1966)

To some people, the sound of children’s laughter is enjoyable and sweet. However, in this gothic horror, it is instead associated with the vengeful ghost of Melissa Graps (Valerio Valeri), a young girl terrorising a small European village in the early 1900s. The story begins when Dr Paul Eswai (Giacomo Rossi-Stuart) arrives to perform an autopsy on a woman who died under perplexing circumstances. As his witness, he has medical student Monica Schuftan (Erika Blanc), a native of the old town. Together they try to determine the cause of death, only to discover something bizarre during the postmortem examination that will lead to more questions than answers as they descend deeper into confusion and the lore of the region.

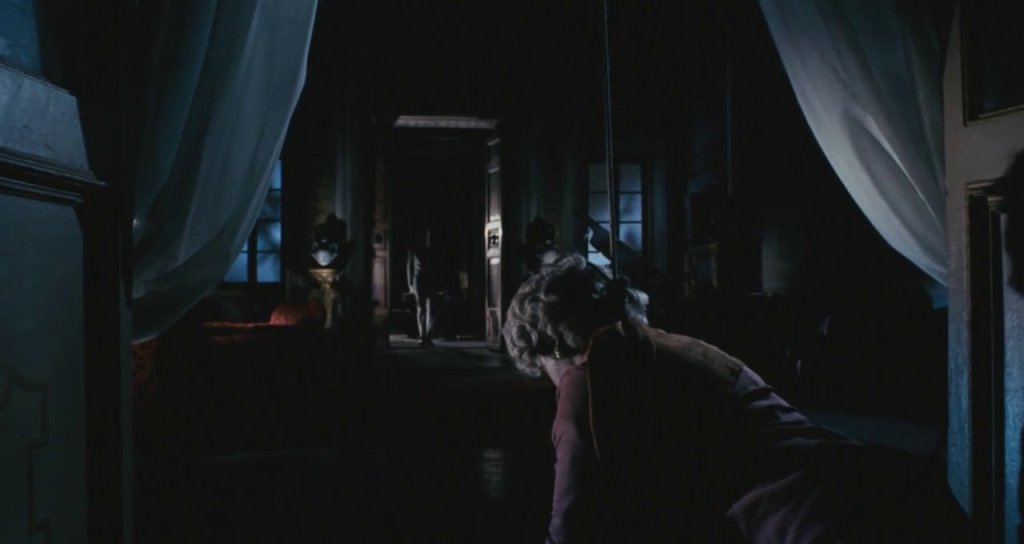

There is something timeless about Bava’s films in that they are something to experience due to their distinct aura and vast world-building. With its cobblestone streets, endless creepy hallways and hypnotising spiral staircase, Kill, Baby… Kill! (original title: Operazione paura) creates a viewing experience filled with a palpable dread that impacts the entire story. The nighttime scenes, with their thick fog and dangling cobwebs, are all examples of how eerie the visual language is. At one point, the camera appears to inhabit the point of view of—and move along with—the movement of a swing, mimicking the motion by zooming in to later lower its position to showcase the vengeful girl on the swing it previously moved along with. Add immersive lighting, lavish costumes, and stunning set design and it is no surprise why the film is such a classic gothic outing.

The script by Bava, Romano Migliorini, and Roberto Natale explores the clash between science and the idea of the inexplicable and more superstitions, as well as the differences between past and present, old-fashioned and modernised. Even though the various characters, including the villagers and Inspector Kruger (Piero Lulli), all have their say in the matter, when someone is out for revenge, neither might be adequate to prevent it. Ultimately, Kill, Baby… Kill! would prove influential within J-horror and for filmmakers Federico Fellini and Martin Scorsese. The sight alone of the blonde girl who wears a formal white dress and bounces a ball became influential, as referenced in FeardotCom (2002). It would not be too farfetched to suggest that David Lynch might have been influenced by this film as well, particularly since there is a surrealistic sequence of Dr Eswai chasing his doppelgänger that feels reminiscent of when Special Agent Dale Cooper encounters something similarly disorienting in Twin Peaks. Apart from its apparent substantial legacy, the film proves that, if used correctly, there can never be too much fog.

Leave a comment